Black Students and Black Studies — JBHE Dismantles the Myth October 30, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African American Students, Black Students, Black Studies, Higher Education, Humanities.2 comments

In a brief report titled, “Banish the Stereotype That African-American College Students Tend to Major in Black Studies,” the current Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (JBHE) weekly bulletin published these findings:

New Department of Education figures on degree attainments show that the stereotypical view of the African-American college student rushing into black studies majors is totally false. Only 1,051, or 0.8 percent, of all African-American bachelor’s degree recipients received their degree in any type of ethnic studies discipline. Therefore, only one out of every 130 bachelor’s degrees awarded to blacks was in ethnic studies. In fact, there are more blacks who majored in the physical sciences — a field in which there are very few African Americans — than African Americans who earned their degree in black studies. There are more than six times as many blacks majoring in computer science and more than five times as many blacks majoring in the biological sciences than in black studies.

I am not sure of the extent to which this stereotype has penetrated the national consciousness. If it is indeed a widely held stereotype that African American college students tend to major in Black Studies, then I applaud the efforts of the JBHE to debunk this belief. I cannot help but question, however, the subtext of this report, that it somehow diminishes Black people to be so heavily associated with Black studies programs.

My perspective, after all, is informed both as my current position as professor in the humanities and a my past experiences as an undergraduate admission officer. As someone who has followed the undergraduate careers of the Black students on at least four campuses with great interest, the fact that there are several times more Black students majoring in the sciences than in an interdisciplinary (and partially humanities-based) degree program like Black studies comes as no surprise. I and most of the African American English majors that I have encounted over my years as a professor have noted with great disappointment the dearth of African American students who choose humanities fields (even the traditionally oversubscribed field of English) as their academic focus.

I and several of my colleagues of color have noticed how much more willing Black students are to major in science and social sciences fields than to ever even consider at major in the humanities or the arts. I am grateful for the existence of Black studies programs, because it is through these interdisciplinary majors that many African American studies get their only exposure to African American literature, U.S. Black and African art, and African American and African dance.

I cannot tell you how many Black economics, psychology, biology, pre-law, and pre-business students I encounter who, in their final year of college — after taking an African American literature or music course as a lark — express regret that they never considered majoring in a literature- or arts- based field.

It is only after such students enter law school, business school, or a post-baccalaureate pre-medical program and encounter classmates who were English, History, Art, Modern Languages, and Ethnic Studies majors that they begin to realize that the critical thinking skills, creativity, and communication skills that are nurtured in many humanities and arts fields can make such programs as practical a choice as a science- or social science-based major.

I understand what is at stake for many African American students. For many students of color, college is not simply a matter of learning for learning’s sake. Many Black students and their families are depending on the increased earning potential and the promise of upward mobility that higher education can provide; but it is my special interest, as a Black professor and mentor, to make sure that students understand the breath of their options.

Success doesn’t have to mean majoring in something that ends in -ology. It might, and for students who have a true passion for one or more of the sciences and social sciences, such plans of study are wonderful choice. But for those who are quietly nurturing a talent in music or art, a love of literature or history or a great aptitude for learning languages, the knowledge that these fields can also provide that all important key to success could very well change their lives.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

A Beautiful (Black) Mind: Lawrence Otis Graham October 26, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in A Beautiful Mind, A Member of the Club, Higher Education, Lawrence Otis Graham, Our Kind of People, Princeton, Proversity.5 comments

The summer before my senior year of high school, Lawrence O. Graham became my best friend. We had never met, and I didn’t even know what he looked like; but during the months of July and August we went everywhere together…sort of. I was in love with his book, the Ten-Point Plan for College Acceptance. I read it backwards and forwards, literally, and before summer was out, I knew Graham’s strategies for admission inside and out; but I also felt like I knew Graham himself.

After I was accepted into the college of my choice — thanks in no small part to Graham’s advice — I began reading his book on college success, Conquering College Life: How to Be a Winner at College. It wasn’t until I was halfway through this book that my mom saw him interviewed on a television talk show. The interview revealed that Graham was young, a recent graduate of Princeton University, and Black; and The Ten-Point Plan for College Acceptance, the book that had been my personal handbook during the college application process, was published when the author was only 19 years old!

That was all my high school heart needed to know. I was in love, in that bff (best friends forever) sort of way. Graham was like me, a bookish, intellectually precocious Black kid who was very serious about college admissions; and on top of all that, Graham was sorta kinda living my dream — while I aspired to be a writer, he already was.

Graham describes his unique approach to finding a publisher for that first book in this interview excerpt, recounted in his profile on answers.com:

[Graham] wrote one book each year until he graduated [from Princeton]. His first, The Ten Point Plan for College Acceptance, required visits to 50 schools in six states, but was completed by the time he finished his freshman year. “I decided to write an article about getting into college,” he said. “No one would publish it because I was an unknown 17-year- old, so I decided to make it into a book instead. I came to New York by bus with two rolls of dimes and started calling publishers from a call box on Park Avenue.” Most publishers’ receptionists laughed when he spoke to them, but he was not discouraged. “I take an entrepreneurial approach to everything,” he later observed. “I NEVER take no for an answer.”

Eventually one publisher suggested he get an agent to help sell his book. Grateful for the advice, Graham flipped the telephone directory from `P’ for publishers to `L’ for literary agents, and opened his second roll of dimes. He had reached “Zeckendorf, Susan,” the next to last name on the list, before getting an appointment, which eventually led to the book’s publication. The Ten Point Plan sold 20,000 copies and earned him guest appearances on the Phil Donahue Show as well as on the Today Show.

In the 25 years since I first encountered The Ten-Point Plan, I have followed Graham’s career with fascinated interest. Lawrence Otis Graham’s career exemplifies the path of the classic polymath (homo universalis, uomo universale), a true renaissance man who is both knowledgeable and highly skilled in many areas.

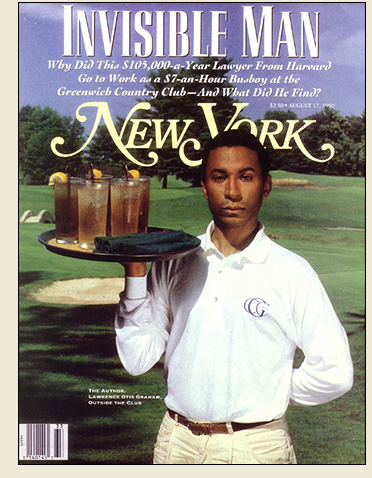

A graduate of Harvard Law School, Graham is employed with Smith, McDaniel & Donahue, a law firm specializing in environmental issues, and he is also president of Progressive Management Associates, a diversity consulting firm. Despite these professional accomplishments, though, it was his groundbreaking and controversial 1992 New York Magazine article on Graham’s experience working undercover as a busboy at the exclusive Greenwich Country Club that launched him on the path toward becoming one of the nation’s most highly regarded commentators on race and integration in the United States.

In his article on the Greenwich Country Club, titled “Invisible Man” Graham revealed an atmosphere deeply entrenched in what has been called genteel racism. Graham’s damning exposé generated a mountain of controversy and a flood of letters, and acquainted a broad cross-section of American readers with the insight and erudition of this previously little-known provocateur.

In the 15 years since the New York Magazine article Lawrence Graham has used his skills of analysis and critique to examine the influence of race and the function of the color line on a variety of institutions, constituencies, and individuals ranging from the U.S. Black elite (in Our Kind of People), to national politics (in The Senator and the Socialite), to the American workplace (in Proversity), to himself (in Member of the Club).

A contributing editor for Reader’s Digest who has written for New York Magazine, The NY Times, Essence, and U.S. News & World Report, Graham has appeared on Today, The Phil Donahue Show, The Oprah Winfrey Show, and WNBC-TV, CNBC, and CNN.

Graham’s unique perspectives may soon make their way to the big screen. Warner Brothers is currently developing “Invisible Man,” his New York Magazine piece on the Greenwich Country Club, into a film starring Oscar-winning actor Denzel Washington.

Graham has been roundly criticized, most notably by author Shirlee Taylor Haizlip, for viewing the struggles and interests of working-class and poor Black people through the lens of elitism. Haizlip opines that when Graham engages the issues and experiences of his working class brethren, “a shared sense of humanity never comes through.” However flawed Graham’s analyses of the lives of working-class and for African Americans may be, his explorations of the origins, customs, mores, and challenges of the African American upper classes, are perceptive and bold, unflinching and candid. I would like to finish this profile with a brief passage from Graham’s Our Kind of People, his study of the Black elite in the U.S. This passage, excerpted from a post in the blog Far Outliers is an example of the author at his best, exploring the movements, attitudes, history, and future of the Black elite.

One can find both pride and guilt among the black elite. A pride in black accomplishment that is inexorably tied to a lingering resentment about our past as poor, enslaved blacks and our past and current treatment by whites. On one level, there are those of us who understand our obligation to work toward equality for all and to use our success in order to assist those blacks who are less advantaged. But on another level, there are those of us who buy into the theories of superiority, and who feel embarrassed by our less accomplished black brethren. These self-conscious individuals are resentful of any quality or characteristic that associates them with that which seems ordinary. We’ve got some of the best-educated, most accomplished, and most talented people in the black community—but at the same time, we have some of the most hidebound and smug. And adding even further to the mix are those of us who feel we need to apologize to the rest of the black world for our success and for being who we are. For me, the black upper class has always been a study of contrasts. –from Our Kind of People

I am certain that Lawrence Otis Graham has touched many lives through his work as an attorney, as a leader in diversity consulting, and as a 2000 candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives (supporters included neighbors Bill and Hillary Clinton); but it is in his capacity as a writer that he has thrilled, challenged, instructed, and inspired me. Even now, a quarter century after I first encountered his work, I still read Graham with a mixture of admiration and pride and more than a little bit of wonder at the talent and productivity of this outstanding mind:

A Partial Bibliography of Books by Lawrence Otis Graham:

-

Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class (2000)

-

The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America’s First Black Dynasty (2006)

-

A Member of the Club: Reflections on Life in a Racially Polarized World (1995)

-

The Best Companies for Minorities: Employers Across America Who Recruit, Train, and Promote Minorities (1993)

-

Proversity: Getting Past Face Value and Finding the Soul of People–A Manager’s Journey (1997)

-

Ten Point Plan For College Acceptance (1981)

-

Your Ticket to Law School: Getting in and Staying in (1985)

-

Jobs in the Real World (1982)

-

Your Ticket to Business School (1985)

-

Youthtrends: Capturing the $200 Billion Youth Market (1987, with Lawrence Hamdan)

Good News on the Enrollment Front October 22, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Achivement Gap, African American Students, Black Youth, Blogroll, enrollment, graduation rates, Higher Education, race.4 comments

The Journal of Black in Higher Education (JBHE) has recently reported that the most current statistics from the U.S. Department of Education (from 2005) find that Black students comprise a full 11.7 percent of all students enrolled in higher education in this country. JBHE notes that, [t]his is nearly equivalent to the percentage of blacks in the college-age population”, and that, “[a] decade earlier, in 1995, blacks were 10.3 percent of all enrollments in higher education.” “Thus,” JBHE concludes, “black progress over the past decade has been nothing short of spectacular. In 1995 there were 1,474,000 blacks enrolled in higher education. By 2005 black enrollments had increased by more than 42 percent.”

Popular perceptions achievement and racial and ethnic difference evolve far more slowly than does the reality of any specific population. Thus, even as the rate of Black enrollment in higher education nears the overall percentage of Americans who are Black (12.9 in the 2000 census), and despite the fact that a full 80% of all African Americans over the age of 25 are high school graduates, U.S. residents of all ethnicities cling to the perception that Black people are persistent underachievers for whom even a high school diploma is a rare accomplishment.

When it comes to popular perceptions of Black people, I am much more interested in how African Americans perceive themselves than I am in how white, Asian, Native American and Latin American people perceive us. Thus, I am most deeply concerned about the negative perceptions that Black people themselves have of our own academic performance and capabilities.

My own interactions with Black people of all ages indicates that many African Americans perceive Black high school graduation rates and Black college matriculation rates to be far lower than they actually are. Indeed, I have had to cite specific sources in order to convince some of my brothers and sisters that their grim view of African American achievement is not necessarily the reality of the situation for all U.S. Blacks.

This is not to say that inequality and inequity do not persist, nor is it to suggest that the Black-white achievement gap does not continue to rear it’s head in college graduation rates and in high school graduation rates, particular in underserved urban and rural communities in the U.S.

I do believe, however, that a more accurate view of the state of Black achievement in higher education — and especially a greater emphasis on Black progress alongside the continued emphasis on areas of struggle) might counterbalance the overwhelmingly negative spin on the relationship of African Americans to all areas of intellectual endeavor advanced throughout both the mainstream and alternative media.

The news about Black folks and education is not all good. But if we begin to emphasize the good alongside the bad, young people who are actively trying to figure out what it means to be Black and what possibilities exist for them as they grow and develop in to African American men and women will realize that the experiences of U.S. Black folks in both secondary and higher education are not monolithic, but are, instead, as diverse as young Black people themselves.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Elementary, My Dear Watson October 21, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, African American Students, African Americans, Black Students, Blogroll, Eugenics, Higher Education, IQ, James Watson, racism, Racism on Campus, SAT, Standardized Testing.2 comments

In the days since I first became aware of Nobel laureate Dr. James C. Watson’s troubling conclusions regarding race and intelligence, I have wondered how I, as an African American professor, could even begin to respond to such reactionary ideas? How does a Black academic respond to comments that proclaim the fundamental incapacity of Black people to succeed academically?

For those who haven’t been following this story, on October 14, The Sunday Times of London published an interview with Waston that included this controversial passage:

He says that he is “inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa” because “all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours – whereas all the testing says not really”, and I know that this “hot potato” is going to be difficult to address. His hope is that everyone is equal, but he counters that “people who have to deal with black employees find this not true”. He says that you should not discriminate on the basis of colour, because “there are many people of colour who are very talented, but don’t promote them when they haven’t succeeded at the lower level”. He writes that “there is no firm reason to anticipate that the intellectual capacities of peoples geographically separated in their evolution should prove to have evolved identically. Our wanting to reserve equal powers of reason as some universal heritage of humanity will not be enough to make it so”.

I am not particularly interesting in addressing Watson’s specific comments about race and intelligence. His racism is disappointing, but not surprising; and those who choose to expend their intellectual energy (and I use that term loosely) on arguing the genetic inferiority of Black folks will not not be convinced of the equality of Afro-diasporic peoples by even the most persuasive arguments and examples. The belief in Black inferiority is less about the science of intelligence (which itself raises more questions about the nature and measurement of intellectual aptitude than it ever has answered), than it is about the politics of culture, difference, and fear.

Professor Biodun Jeyifo, an African and African American studies professor at Harvard says just as much in a brief interview printed in yesterday’s issue of the Crimson:

[A]lthough [Jefiyo] was vehemently against Watson’s comments, he was not surprised by them.

“It’s not new,” Jeyifo said in an interview. “It’s a very small group of scientists who use their eminence to advance the most regressive views on race and intelligence.”

“He is using his scientific eminence to advance his own political and social views as a citizen,” he added.

Like Jefiyo, the most that I wish to express in addressing the specific content of Watson’s comments is to name them as what they are, a self-serving attempt to promote his own racist views by cloaking them in the language of pseudoscience.

Far more interesting and relevant to me are the larger questions raised by Watson’s most recent gaffe. As Jefiyo reminds us, Watson is not alone in his racism, but is instead part of a small but persistent group of scholars who advocate racist and eugenicist beliefs from within the academy. Their presence, while distasteful to many, is tolerated; and although few non-Black professors would care to acknowledge it, their belief — that Black people are intellectually inferior to whites — underlies much of the harassment and discrimination that Black faculty and students experience on today’s college campuses.

The extreme nature of Watson’s expressions of this belief should call our attention to it’s less overt forms, manifested in all of those little obstacles that suggest both subtly and not so subtly that the college or university campus is not a space for Black people. From harassment by campus police (who often mistake Black college students for criminals and interlopers), to the relegation of fields like Black studies to the realm of program (rather than department), to the slyly articulated suggestions made to Black students and faculty alike that were it not for affirmative action they would not even be on campus, people of African descent enter the campus community keenly aware of the prevailing assumptions about Black intelligence and achievement.

Would a zero-tolerance policy toward research on the links between race, intelligence, and achievement serve in some way to decrease the prevalence of anti-Black racism on majority white campuses? How is such research treated as anything but hate speech? How can Black scholars ever enter the ream of academe as true equals when the academy tolerates (even as a small and marginalized sub-specialty within the life sciences and social sciences) research that seeks to link brain capacity and ethnic identity.

One other question that Watson’s assertions raise for me is based on my consideration of the bases for his research. Anyone who has attended U.S. primary and secondary schools is familiar with the widespread phenomenon of intelligence and “aptitude” testing. I am not speaking of standardized, subject-specific achievement tests like the SAT II, the New York State Regents testing program, or the AP exams. I am speaking of IQ testing, PSATs, and SATs. For reasons that are not completely clear to me, these exams also note the race of each examinee.

I have always enjoyed taking intelligence and aptitude exams, in the same way that I enjoy sudoku, crossword puzzles, Jeopardy, and similar challenges; but, looking back on my academic career, I cannot easily identify any benefits that I gained from taking these exams, even as a so-called “good tester.” As a high school senior, for example, my SAT scores, indicated nothing to college admission officers that SAT II and AP exam scores, course grades, and teacher recommendations could not have conveyed.

Also, as a former undergraduate admission officer, I can say that the correlation between high SAT scores (and IQ scores) and high academic achievement has many exceptions. The skills and thought-processes involved in doing well on aptitude and intelligence differ substantially from the skills required to manage a challenging academic courseload and to do well in college courses; I can still recall many applications that reinforced to me that high SAT scores did not necessarily translate into high grades in honors and AP courses.

Of course, not all testing is undertaken to demonstrate a student’s readiness for college work. Keeping that in mind, I can certainly concede the need for reliable tools for diagnosing learning disabilities, especially in order to address the needs of and to make accommodations for students with different learning styles. Even so, IQ is not a necessary tool for performing such diagnoses, as more directed forms of testing that identify particular perception-, comprehension-, processing-, and computation-based challenges would go much farther toward addressing the specific obstacles that inhibit a young (or not-so-young) person’s ability to have success in the classroom and in the workplace.

The point of all this self-examination and reminiscing is to ask the larger question of why intelligence testing is even necessary. I could advocate for the elimination of the racial classification of test-takers, but such a minimal step would fail to challenge and disrupt the intelligence and aptitude testing establishment sufficiently to bring and end to this practice. Neither high nor low scorers on IQ and aptitude exams benefit significantly from research and testing in this area, nor are the interests of a democratic, multi-ethnic society served by intelligence researchers’ obsession with race as a causal factor.

While I am in no way surprised by James Watson’s beliefs, his comments reinforce for me the need for a fundamental shift in how we in the west engage issues of difference. Let the 21st century be the century in which research on the links between race and intelligence in particular and IQ and aptitude tests in general join the ranks of the iron maiden, the hangman’s noose, phrenology, and alchemy as practices and disciplines that we have deemed markers of the barbarism and ignorance of previous generations. Let’s these forms of testing and research come to and end, and let us move on into a more progressive and more pluralistic future.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Racist “Pranks” and Jena Fatigue October 19, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Higher Education, Jena 6, Kristy Smith, Noose, Peggy McIntosh, University of Louisiana, White Privilege.1 comment so far

“It wasn’t that we were making fun of the Jena 6 incident. We were just fed up with it… I have just as many black [friends] as i do white. And I love them to death.” — University of Louisiana-Monroe student Kristy Smith, whose Facebook.com page shows students in blackface, apparently acting out the beating of Jena High School student Justin Barker.

The events surrounding the arrest and charging of the Jena 6 has sparked at least two copycat incidents on U.S. college campuses, including Ms. Smith and her friends’ parody performance of the beating that led to the Jena 6 arrests on her Facebook page.

Subsequent Jena 6 inspired episodes of campus racism include a noose found hanging outside of the University of Maryland Black Cultural Center and a noose found hanging from the doorknob of Columbia University professor Madonna Constantine.

In her noted essay, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” scholar Peggy McIntosh notes that one of the benefits that she, as a white woman, experiences as a result of white privilege is that she “can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color, who constitute the worlds’ majority, without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion.” Revise this sentence to read, “I can remain oblivious of the language and customs and perspectives of persons of color,” and I believe that we just might have uncovered the roots of these copycat incidents of racism that have popped up in repsonse to the Jena 6 trial and protests.

If white privilege means being able to remain oblivious to feelings and beliefs that people of color have toward major social and political issues and events, then prominent cases like the Jena 6, whose wide media coverage is virtually impossible to ignore, destabilizes the conventional relationship between white people and people of color by forcing white people into direct contact with the perspectives of African Americans. The widespread coverage of the Jena 6 protests — on the major networks and on cable, on internet news sites and blogs, and on radio news — compromises the usual ability of white and other non-Black Americans to read or hear Black perspectives selectively, at the the time, under the conditions, and on the topics of their choosing.

Responding to the widespread criticism of her online blackface performance, Kristy Smith, explained that she and her friends were “just fed up with [the Jena 6 case and/or coverage].” The subtext of this statement is that she was “just fed up” with having to deal with people and ideas that are so different from her own. So too were the as yet unidentified culprits behind the noose displays on the Columbia University and University of Maryland campuses.

I am betting that these unknown perpetrators would, if found and confronted, express a smiliar “Jena fatigue,” a not-so-rare psychological condition that spreads rapidy with racial, class-based, religious, or sexual majority populations when the issues and perspectives of an otherwise underrepresented minority group take center stage (usually as a result of an act of overt racism, classism, sexism, or homophobia). Symptoms include fatigue and frustration in the effected majority groups, most often over the loss of the ability to pretend that their ideas about race are universally shared by all. Risk factors include narrow-mindedness and race, class, gender, sexuality, and/or religious majority status.

Note: People of color, gays, Muslims, Jewish people, poor people, and women may all find themselves at risk for developing this affliction when and if the majority groups that they belong to are forced into contact with the perspectives of members of the corresponding minority (think wealthy and middle-class and/or people of color, white and/or wealthy women, wealthy white gay people, etc.)

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Affirmative Antics October 6, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, Affirmative Action, African American Students, African Americans, Black Students, Higher Education.add a comment

I have watched the last decade’s public debate over affirmative action with both interest and disgust. I have observed the hysterics over the admission of “less qualified Blacks” through “racial preferences” and “quotas” with what is best described as an attitude of interest and cynical amusement. Majority fears of the Black-skinned “Other” encroaching upon the places that white America holds dear (the plantation household of yore, the union shop, the public high school, and — most recently — the college campus) is neither new nor surprising, nor is the denial of racism or the refusal to implement strategies for addressing not for past racism, but racism now, in the present.

Appalling, though not surprising, has been the lack of an uproar and, in many cases, the outright defense of affirmative action for other groups within the college applicant pool. I am speaking particularly of those widely known but only grudingly acknowledged systems in place at U.S. colleges and universities to accord preferential status to wealthy students, athletes, and the children of alumni.

Many college administrators, alumni, and athletic directors have argued that these students are good for the colleges that they are admitted to and — ironically enough — that they add an important element of diversity to the student body.

I believe that both institutions and the students who attend them do indeed have much to gain from enrolling students who represent a wide range of experiences and incomes, talents and passions. You may be surprising to learn that I even believe that colleges can make a compelling argument in favor of cultivating multi-generational relationships and family loyalties through legacy admissions.

In short, I believe that all of the elements of a student’s background and identity should be taken into account when weighing an application for college admission, including family income, parents’ education, legacy status, region, nationality, ethnicity, and race. These factors should not overshadow more academic criteria (grades, high school curriculum, teacher recommendations, standardized test scores), but they do matter, as much as any other factors that shape a students’ pursuit of educational success.

Whether motivated by a single-minded fear of the browning of American, or simply by a misguided believe in the possibility (in this ever-so-subjective world) of a purely merit-based admission process, the nation’s most vocal opponents of race-based anti-affirmative action remain largely silent with regard to the preferences given to athletes, wealthy students, and legacy applicants receive.

And yet a recent study conducted by two Princeton University sociologists and described in the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education suggests that while the financial boons and loyalties that at least one of these non-race-based preference groups brings to college campuses may serve an institution’s economic interests, the admissions preferences grant to legacy applicants may conflict witha college’s academic profile and mission.

On most selective campuses, legacy admits (few of whom a people of color) significantly outnumber African American admitted students, despite the much greater interest on the part of affirmative action opponents in ending race-based consideration than on addressing legacy or income-based preferences. For those who are uncomfortable with the hypocrisy of this stance, here is some information that might bolster your position.

JBHE reports:

Now two sociologists at Princeton University have found that students who received admissions preferences because of their ancestors’ relationship with the institution are more likely to run into academic trouble than African Americans who were admitted under affirmative action admissions programs. They say that legacy admits whose SAT scores and high school grade point averages are far below the mean for all entering students are more likely to get poor grades in college than black students admitted under race-sensitive admissions. The study also found that at the colleges and universities where legacy admits seem to have the most advantage, the dropout rates for legacies are the highest:

In contrast, blacks who received admissions preferences did not have similar levels of poor grades and were just as likely as other blacks to stay in college and earn a degree.

The study, which is published in the journal Social Problems, did find that at the selective colleges they surveyed, 77 percent of black students were the beneficiaries of affirmative action whereas 48 percent of all legacies benefited from admissions preferences.

Posted by Ajuan Mance