Black Alumni on the M-I-C February 21, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African Americans, Black Colleges, Black Students, Blogroll, Higher Education, Hip Hop, race.add a comment

Today we celebrate these Black hip hop and R&B stars and their alma maters —

- Chuck D (Public Enemy) graduated from Adelphi University in 1984. At Adelphi he studied graphic design and was a college radio DJ. Asked about the importance of earning his Bachelor’s degree, Chuck D responded that “graduating from college in 1984, now that’s my greatest accomplishment.’’

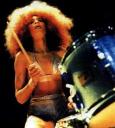

- Cindy Blackman (drummer, Lenny Kravitz) earned her Bachelor’s in Drums from Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music in 1980.

Cindy Blackman

- Amerie earned her B.A. from Georgetown University in 2000, with a double major English and Fine Arts.

- Tatyana Ali earned a B.A. from Harvard University in 2002.

- Roberta Flack graduated from Howard University in 1958, at the age of 19. She entered Howard University at the age of 15 on a full music scholarship.

- DJ Amp Live and MC Zion (of Oakland-based rap group Zion-I) earned their Bachelor’s degrees at Morehouse College where they first met and began working together.

- Sister Soujah earned her B.A. at Rutgers University, where she doubled majored in American History and African American Studies and participated in a study abroad program in Spain.

- Tajai (Souls of Mischief) graduated from Stanford University in 1997.

- Young MC (Marvin Young) graduated from the University of Southern California with a Bachelor’s in Economics.

Blackness Visible, Part III (“You’re Black, but You’re Not Really Black”) February 20, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African Americans, Black Students, Higher Education, race, racism, Stereotypes.5 comments

“You’re Black, but you’re not really Black.”

If you are Black person in the U.S. and you have spent time as a student on a predominantly white college campus, you are probably familiar with this all-too-frequent observation. It is most often expressed by a white or otherwise non-Black classmate/roommate/teammate to a student of African descent who somehow seems to exhibit qualities, speak in ways, and/or demonstrate interest in things that the non-Black speaker associates with whiteness. The text-to-subtext translation of this phrase is: “I have an idea in my mind of what Blacks are like, and some of the things you say and do seem to contradict some of the things I thought I understood about you people.”

The following is only a partial list of the qualities, ways of speaking, and interests that might invite such a comment from the non-Black observer:

Qualities/Characteristics: courtesy, sophistication, nerdiness, conservatism, open-mindedness, clumsiness, grace, industriousness, contemplativeness, modesty, intelligence, ingenuity.

Ways of Speaking: with a midwestern accent; with a “valley girl” accent; with a southern California surfer accent; with a Boston/Rhode Island/Southern New England accent; with a British accent; with a French accent; with a Cuban; Dominican, Puerto Rican, or Brazilian accent; in a language other than English; in English — but with no discernible ethnic or regional accent; using no particular form of ethnic or regional slang; using skater slang; using San Fernando Valley slang; using Canadian slang; using Cockney or any other form of British slang; in Latin, in ancient Greek; using a large standard English vocabulary.

Interests: reading, writing, mathematics, science, history (including Black history), art, literature (including African American literature), any type of music that is not contemporary hip hop or R&B, ballet, modern dance, musical theatre (strangely enough), drama, traveling, hiking, cycling, skiing, golk, jai alai, crew, field hockey, squash, any sport that is not football or basketball, journalism, philately, spelunking, scuba, chess, Dungeons and Dragons, archery, the Society for Creative Anachronism.

One of the most recent public declarations of the “you’re-black-but-not-really-black” variety occurred when presidential apsirant Joe Biden described fellow candidate Barack Obama as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.” So, I supposed you could add to the list of qualities and characteristic cleanliness and beauty.

As you can see, it would be easier for me to list the limited range of qualities, ways of speaking, hobbies and interests that are associated with Black people than for me to list the range of items and activities that are suggestive of NRB status (NRB = not really Black). Unintentional or otherwise, the effect of this long-standing practice of locating certain activities, interests, and styles of communication in the realm of whiteness is that when Black people display these behaviors, preferences, interests, and characteristics their visibility as Black is suddenly compromised.

It’s not that they look less like African Americans from a physical perspective. The many wonderful characteristics that function as bodily signifiers of your African ancestry will remain in place no matter how many times you listen to the Dead Kennedys’ Bedtime for Democracy album.

No, it’s not that Black people look physically less Black when they manifest those interests, qualities, or styles and modes of communication that whiteness has claimed as its own. Rather, it’s that whiteness — as a socially constructed identity — depends heavily for its meaning on the location of Blackness as its opposite; and thus it is less challenging to the meaning and position of whiteness to interpret the Black student’s expression of so-called “white interests” as marking him/her as somehow less Black than it would be to recast said activities as less white.

Stated more simply, the total abandonment of the binary system that defines some interests and behaviors as white (usually those associated with intellect, erudition, morality, normalcy, and dominance) and some as Black (usually those associated with physicality, sexuality, violence, abberation, and submission) would threaten the socio-political and cultural power–and, therefore the very meaning–of whiteness (as center and norm). Thus it is safer — so to speak — for white people to label Black people who manifest those interests and behaviors associated with whiteness as somehow less Black than it would be to label those interests and behaviors as not particularly white.

On college campuses this trend has had a very curious effect. Simply by virtue of his engagement in an intellectually-based enterprise, the Black college student is always already a challenge to prevailing definitions of whiteness. His or her engagement in the everyday activities that define student life — attending classes, studying at the library, taking exams, etc. — constitues a challenge to the self-perception of all those who identity is dependent on the understanding that white people are intellectually superior to people of African descent.

Rather than embrace the notion that erudition and intellectual curiousity are evident in all ethnic groups, some white students act out against African Americans and other Black people in their on-campus community, publishing songs, cartoons, and other “comic” material (like the affirmative action carol “O Come All Ye Black Folk”) that reinforce their association of Blackness, not with the stately buildings and well-manicured grounds of the college campus, but with the perceived squalor and violence of “the ghetto.”

Similarly, white students’ gangster- and ghetto-themed parties undertake to reinforce the meaning of Blackness as anti-intellectual, impoverished, hypersexual, hypermasculine, and violent as defense against the challenge to whiteness leveled by the presence of Black students in their classes, their dorms, their libraries, and their dining halls.

White students have long decried the tendency of Black students to sit together at the campus dining hall, asserting that such behavior is segregationist and a manifestation of “reverse racism.” I believe that the unacknowledge and, in many cases, sub-conscious objection to Black students sitting together in the dining hall lies in its particularly pointed challenge to the longstanding association of the college experience with white (intellectual and moral) supremacy.

Despite the personal annoyance that Black students experience whenever they are labeled as NRBs by their white counterparts, the greatest danger posed by categorization of some behaviors and interests as white and some as Black is based far away from the hallowed halls of academe, in those editorial meetings, on those film and video sets, and at those recording studios where the image of the Black as hypersexual, anti-intellectual gangsta, pimp, thus, welfare mama, or ‘ho’ is created and disseminated.

These images pose a threat to increased Black access to and success in higher education, not because of the ways that they shape white perceptions of Black people, but because of the ways that they distort and limit Black people’s perceptions of themselves.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Slavery on Campus, Part I: UNC Chapel Hill and Yale University February 20, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African Americans, Black History, Higher Education, Ruth Simmons, Slavery.1 comment so far

With these words, Brown University president Ruth J. Simmons brought national attention to the question of the role and relevance of slavery in U.S. higher ed history. Her leadership on this topic has become a touchstone for a national discussion of the role of slave labor, slavery profits, slave owners, and pro-slavery partisans in America’s colleges and universities.

I spent some time searching the internet to see how and when institutions used online media to address the role of slavery on their campuses. Here is some of what I found:

1.UNC Chapel Hill: This institution is a model of full disclosure. As part of the UNC Chapel Hill Virtual Museum, the University has created an online exhibit titled “Slavery and the University.” This fascinating and highly accessible website, complete with photos and profiles of both UNC-related slaves and slaveholders, provides a detailed account of the relationship of slavery to the institution’s growth, during those key years prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. I highly recommend this site as a bold and informative exploration of the links between the institution of slavery and U.S. higher education, this from a southern university whose ties to the peculiar institution are quite deep.

Slavery played an integral role in the establishment and maintenance of the college, its funding, and the financial well-being of key faculty, students, presidents, and trustees. Several existing campus buildings were built by slaves, and there are campus buildings named after slaveholders.

- Old East (the first building erected on campus), Old West, and Gerrard Hall were built by enslaved Black people.

- University presidents Joseph Caldwell and David Swain owned slaves.

- Even faculty from outside the South like Englishman James Phillips and Connecticut native Elisha Mitchell purchased slaves after moving to Chapel Hill. Rev. Phillips conducted religious services for slaves on Sunday afternoons and helped build a shed for slave worship behind the Presbyterian church. In 1919, the university named its new mathematics building in honor of James Phillips and two of his relatives.

- The university’s antebellum trustees were typically large slaveholders. Of the original forty trustees appointed in 1789, at least thirty owned slaves. Among them, Benjamin Smith of Brunswick County owned the most with 221. In 1851, the university named a library for Smith that is now known as PlayMakers Theatre. Other trustees with substantial numbers of slaves included Stephen Cabarrus, Samuel Johnston, Willie Jones, and Richard Dobbs Spaight. In addition to being trustees, Spaight signed the U.S. Constitution for North Carolina, and Johnston was the state’s first U.S. senator. Johnston, Smith, and Spaight also served as governors of North Carolina.

- University trustee Paul Cameron was North Carolina’s largest slaveholder in 1860 and one of the wealthiest men in the South. He owned 12,675 acres of land and 470 slaves in Orange County, North Carolina, as well as plantations in Alabama and Mississippi. Cameron was a political ally of President David Swain, who contributed funds to reopen the university after the Civil War and then to construct Memorial Hall. Cameron Street, a street named for this highly problematic figure, runs through the center of campus.

2.Yale University

Yale University is another model of candor and culpability around the issue of slavery and institutional history. The degree to which the legacy of slavery is intertwined into the life of contemporary Yale students — in the form of building names, fellowship funding, and other aspects of Yale life — is quite surprising, especially for a Northern university that prides itself on fostering and valuing the highest levels of intellectual development.

- According to the Yale slave history website, between the 1930s and 1960s, Yale chose to name most of its colleges after slave owners and pro-slavery leaders. Here is a list of the colleges so named:

Berkeley College

Calhoun College

Davenport College

TD College

JE College

Morse College

Pierson College

Saybrook College

Branford College

Silliman College

Stiles College

Trumbull College

Divinity School

Law School

Street Hall

Woodbridge Hall

- Yale’s first endowed professorship, the Livingstonian Professorship of Divinity, was established with a donation from Col. Phillip Livingston, a prosperous slave trader.

- Similarly, Yale’s first library fund, and first scholarship fund were established using donations from 18th-century slaveholders.

- Yale also graduated several men who would become prominent abolitionists, including Samuel Hopkins (class of 1741), James Hillhouse (1773), Cassius Clay (1832), and Charles Torrey (1833).

One of my goals in sharing this information is to foster the spirit of full disclosure. Today’s college campuses are a hotbed of debate on issues of race, ethnicity, and privilege and the relationship of all three to U.S. higher education. Far too often, the subtext of such debates is the idea that the influx of unprecedent numbers of people of color has politicized and racialized the college campus in ways that detract from the overall mission of the institution, the dissemination of objective knowledge. To understand the degree to which slavery, pro-and anti-slavery debates, and related issues played a role in the establishment of many of our nation’s oldest institutions of higher learning is to re-contextualize contemporary debates around race and ethnicity on campus as simply the most recent chapter in a centuries-old discussion, carried out in the boardrooms, classrooms, and chapels of U.S. colleges and universities.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Interesting Link and Test Post February 19, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African Americans, Black Youth.1 comment so far

<a href=”http://technorati.com/claim/i2q6psmkxx” rel=”me”>Technorati Profile</a>

…and click this link for an interesting article on some Black parents’ efforts to combat what would best be described as the ravages of internalized gangsta-ism in their middle-school-aged boys.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Black Higher Education Firsts and Other Milestones, #1 February 19, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, African Americans, Black Colleges, Black History, Black Students, Blogroll, College Presidents, Higher Education.add a comment

Here are the most recent additions to the Black Milestones in Higher Education timeline that I maintain over at twilightandreason.com:

1838 — Andrew Harris becomes the first African American to graduate from the University of Vermont.

1867 — Robert Tanner Freeman becomes the first African American to earn at dental degree from an American college or university (Harvard University).

1874 — On July 31st of this year, Rev. Patrick F. Healy, S.J. becomes the first African American president of Georgtown University.

1877 — George Washington Henderson, long thought to be the first African American to graduate from the University of Vermont, becomes the second African American to graduate from the University of Vermont. Henderson graduates first in his class and becomes the first African American ever to be elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. Edward Bouchet, the first African American to graduate from Yale University, and long thought to be the first U.S. Black person ever elected to Phi Beta Kappa, was actually voted into the prestigious honor society several years later, in 1885.

1937 — Dwight O.W. Holmes becomes the first African American president of Morgan College (later Morgan State University), in Baltimore, Maryland.

1958 — Clifton Wharton (who in 1987 became to first African American to head a Fortune 100 company) becomes the first African American to earn a PhD in Economics from the University of Chicago.

1978 — Dr. Clifton Wharton becomes the first African American Chancellor of the State University of New York System.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

The Color of Deception: The Truth About Race-Based Scholarships February 17, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in African Americans, Black Students, Blogroll, Current Events, Higher Education, racism.9 comments

According to a national study by the General Accounting Office, less than four percent of scholarship money in the U.S. is represented by awards that consider race as a factor at all, while only 0.25 percent (that’s one quarter of one percent for the math challenged) of all undergrad scholarship dollars come from awards that are restricted to persons of color alone.

— from “A Particularly Cheap White Whine: Racism, Scholarships and the Manufacturing of White Victimhood” by Tim Wise on www.civilrights.org

This passage raises some important questions about the things we know and the things that we think we know about race and higher education. The construction of the white college student as victim of so-called “reverse racism” is the equally troubling counterpart to the stereotype of the African American college student as the always already underprepared, academically unqualified, preternaturally anti-intellectual, affirmative action admit.

It is hard to say which is more dangerous, the depiction of the Black student as intellectually inferior beneficiary of biased admissions and scholarship programs or the public depiction of the white student as victim of wrong-headed attempts to diversify college campuses. I am certainly a lot more disturbed by the latter, possibly because the stereotype of the Black simpleton has been such a deeply entrenched component of the white, western cultural mythos that it is no longer shocking to me.

The “manufacturing of white victimhood” is also more disturbing to me because of what it says about notions of entitlement. Given that the overwhelming majority of U.S. college students are white, and considering that white students receive the bulk of all federal and privately-funded financial aid, the notion that even this much abundance feels like oppression to many white people in higher education speaks volumes about the degree to which higher education is still raced in this country. For far too many white students, any encroachment by students of color into academia — even small gains in minority student populations, and even small amounts of minority-specific financial aid — feel like too much.

The small inroads that African Americans and other people of African descent have made into undergraduate populations could hardly be construed as a “browning of academe”; and yet for white and other non-Black students, who have come to associate academic excellence with the absence of Black students, even a handful of African Americans, funded by an infinitesimal proportion of all available scholarship dollars diminishes the specialness of the intellectual enterprise.

As I contemplated how it has come to pass that one quarter of one percent of all scholarships awarded to somewhere around 14 or 15 percent of all undergraduates* constitutes the vicimization of white college students and applicants, I began to compile a list of some of those scholarships that either express a preference for or are exclusively awarded to U.S. members of white, European ethnic groups. As Chris De Morsella notes on MulticulturalAdvantage.com, “scholarships that are targeted towards some group or another literally number in the millions. The overwhelming majority of these scholarships are NOT targeted towards minority groups.” These scholarships rarely draw the ire of those outside of the specified ethnic groups, despite their openly expressed preferences. For a more detailed exploration of the backlash against minority scholarships, check out Chris de Morsella’s “One Million White Ethnic Scholarships Don’t Trouble Student Group Protesting Minority Scholarships.”

Here is just a sampling of what I came up with, along with the exclusionary language provided by the scholarship administrators themselves:

- The Emanuele and Emilia Inglese Memorial Scholarship for “an Italian American undergraduate student who traces his/her ancestry from the Lombardy region and is the first generation of his/her family to attend college.”

- The August Society Scholarship Program, “designed for students of Italian Heritage.”

- The Albert and Emma C. Martocchio Scholarship, for “undergraduate students attending Providence College who are of Italian descent. “

- The Andrea Vicini Memorial Scholarship, for which “preference will be given to students of Italian descent.”

- Ben Landriscina Scholarship, for “undergraduate students of Italian descent attending Pace University.”

- Fieri Bronx-Westchester Scholarship, for “Italian American college students living or attending a college located in the Bronx or Westchester.”

- Astrid B. Cates/Myrtle Beinhauer Fund Scholarship, for “applicants enrolling in post-secondary training or education including trade school, vocational school or college,” and who are “current Sons of Norway members, children or grandchildren of current Sons of Norway members.”

- Camille Collette Daughters of Norway Scholarship, for students of “Scandinavian Heritage”

- Finnish American Social Club Scholarship, for “graduating seniors of Finnish heritage; especially to study history, political science or economics.”

- Hellenic University Club of Philadelphia — “All applicants must be of Greek descent, U.S. citizens, and lawful permanent residents of Berks, Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Lancaster, Lehigh, Montgomery, or Philadelphia Counties in Pennsylvania; Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester or Salem Counties in New Jersey.”

- Hellenic Times Scholarship Fund — “Applicants must be of Greek descent, and between the ages of 17 and 25 as of May, 2007.”

- Hellenic Society Paideia of Virginia — The applicant “must be Greek or Greek-American attending an accredited four-year College or University located in Virginia.“

- The Hellenic University Club of New York, for students of “Hellenic ancestry.”

- Hellenic Professional Society of Texas — “Applicants are eligible for a scholarship if they are currently attending or have been accepted by a college or university in Texas, have shown excellent scholastic performance in their corresponding fild of study, and are of Hellenic heritage. The Society may also consider applications from students of non-Greek descent that have demonstrated clear, strong and sustained excellence in academic studies related to Greek letters or affairs.”

- The Daughters of Erin Scholarship — Applicant “must be a junior or regular member in good standing who has demonstrated a commitment to the goals and mission of The Daughters of Erin through their active service to the organization for at least one year prior to applying for the scholarship.” Daughters of Erin is described as “Central Ohio’s Irish-American Women’s Organization.”

- Irish American Home Society Scholarship, for “members or sons/daughters of ‘members in good standing’ (paid dues to date) of the Glastonbury Irish-American Society. This membership must be active for the past 3 years for eligibility.”

- The Polish Scholarship Fund, Inc. — “Students are eligible who are of Polish descent, who have resided in Central New York in following counties: Cayuga, Cortland, Madison, Oneida, Onondaga and Oswego for a minimum of two years and who have been accepted for admission to any accredited college, university, or training school as a full time student.”

- Massachusetts Federation of Polish Women’s Clubs, for “United States citizens of Polish descent and Polish citizens with permanent residency status in the United States who are undergraduate students, and are members of the Massachusetts Federation of Polish Women’s Clubs.“

- St. Andrews Society of Washington, D.C., — “Scholars must be of Scottish birth or descent.”

- Cajun French Music Association Scholarship — “to apply for this scholarship, applicant must be a member, or a child, grandchild, or great-grandchild of a member in good standing of the Lafayette Chapter of the Cajun French Music Association.”

*In the year 2000, roughly 14 percent of all U.S. undergraduates identified as Black or African American (U.S. Census).

Posted by Ajuan Mance

UNC-Greensboro Graduation Rates a Mixed Bag February 13, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, African American, African American Students, Black Students, Blogroll, gender gap, Higher Education, UNC-Greensboro.add a comment

News and Notes, NPR’s African American news magazine, ran a very interesting report today that focused on African American graduation rates at the University of North Carolina at Greenboro. The Black student graduation rate at this UNC branch is almost equal to that of white students, a very unusual state of affairs for a large state university.

This is refreshing news, but even more surprising is the fact that African American women at UNC-Greensboro have a higher graduate rate than any other ethnic group on campus, including white students. Sadly, this is not the case for African American men on campus, whose graduation rate is lower than both the all-campus rate and the rate for Black women students.

The struggles of Black male students at UNC-Greenboro are part of a larger underachievement trend for all males on this campus. White males at this UNC branch, for example, graduate at a rate of 43% (incidentally, the national average for all Black students).

Much has been made of the gender achivement gap in education, which pervades all levels of academic work, from grammar school to college. In the U.S., this gap is much more exaggerated in African American communities than in white communities, but it is cause for alarm in all of the populations in which it can be detected.

Many observers of the gender achievment gap note that on average, girls have always done better in school than boys have, that boys have always been more likely to be suspended, to be expelled, and to repeat grades than girls have, and that boys have always been more likely to drop out of school. Boys have always been more likely than girls to present with learning disabilities, and stuttering and other language processing and speech-based disabilities are always more common in males than in females.

And yet the implications of this gender achievement gap are very different today than they were even 10 or 15 years ago. It is becoming less and less possible to earn a liveable wage without a college education; and there are even less options for people who do not complete high school.

Though there may always have been an achivement gap in school performance between boys and girls, changes in the economy, increasing advances in technology, and the rise of globalization have created a world in which this historic difference has much more troubling consequences than ever before.

Add to the mix the racial obstacles faced in the workplace by African American women and men at all levels of education, and the issue becomes quite clear. Men are an integral part of the Black community, entering our lives as fathers and husbands, brothers and sons, colleagues, neighbors, and beloved friends. The gender achivement gaps hurts everyone; but in the African American community, the wounds cut much more deeply.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Black Graduation Rates Reach Historic High February 12, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, African American Students, Black Students, Blogroll, Current Events, Harvard University, Higher Education, Ivy League.5 comments

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (JBHE) reports that Black college graduation rates are currently the highest they have ever been, at 43%, an increase of 4 percentage points since 2003. Still, this rate remains a full 20 points behind the graduation rate for white students (63%).

The more closely we examine these numbers, the more curious they seem. For one thing, the graduation rate for Black women, at 47%, is a full 11 points higher than the graduation rate for Black men (36%).

An additional and equally surprising part of the story is exactly where Black students are having the most success (as measured by graduation rates). Recent anti-affirmative action rhetoric suggests that admitting African Americans and other people of African descent to selective colleges and universities does them a disservice, as it abandons them to fend for themselves in an academic environment in which the expectations for performance and skill far outstrip their capabilities.

Black graduation rates, however, tell a very different story. The following charts (from the current issue of JBHE) reveal that Black graduation rates are highest at the nation’s most selective institutions. In fact, at a handful of these institutions African American graduation rates are not only much higher than the Black national average of 43%; they are also higher than white graduation rates at the same schools. The chart immediately below lists the U.S. colleges and universities with the highest Black student graduation rates:

The chart below ranks selective U.S. colleges and Universities from the smallest disparity between Black and white graduation rates to the largest (beginning with those institutions at which the Black graduation rate is higher than the white graduation rate):

(Click on this thumbnail for a larger image)

JBHE explains the significance of these high graduation rates for Black students at selective institutions:

All told, there are 36 high-ranking colleges and universities that have a favorable black-white graduation rate difference of eight percentage points or less. Three years ago there were only 30. Five years ago only 16 high-ranking colleges and universities had a graduation rate gap of eight percentage points or less. This is a strong sign of progress.

Of these 36 institutions with the most favorable Black-white graduation rate difference, Oberlin College had the lowest graduation rate for Black students, at 78%. Curiously enough, this graduation rate was higher than the HBCU with the highest graduation rate (Spelman College, at 77%).Interestingly enough, the HBCU with the highest graduation rate, Spelman College, also happens to be the most selective.

The question that naturally arises from these numbers is: Which institutions are better equipped to serve African American undergraduates, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) or highly selective, majority white institutions?

I suspect that the answer to this question will be found in a discussion of the impact of class and resources (class size and the social and economic class of the students in question on the one hand; and the resources that an institution applies to financial aid and to the cultural, academic, and social support of its Black undergraduates).

In my experience, financial issues are the primary reason that students of color leave college. Financial challenges play a much greater role in student of color attrition than academic failure ever does…which brings me back to the relative success of selective institutions in retaining and graduating their Black students. It’s no secret that these institutions, in their efforts to attract the most academically able, also happen to attract the most financially able. And with their massive endowments, these colleges are among those institutions best prepared to provide a financial safety net that can enable students to stay focused on preparing for their futures, even when their family’s financial present is shaky.

Black-white test score comparisons aside, among U.S. students of African descent there is a strong correlation between class privilege and/or parents who are college-educated and stronger performance in the classroom and on exams like the SAT. This is a bias that is rarely discussed among both opponents and proponents of standardized admissions testings; and yet it goes a long way toward explaining the difference in retention rates between HBCUs and selective institutions.

HBCUs have built their collective legacy on the practice of believing in those students for whom traditional institutions would have no use, including those whose academic and personal profiles indicate more potential ability than actual demonstrated achivement. Often enough this leap of faith pays off; but with greater risk come greater rates of failure. Take a chance on more students whose aspiriations are their primary credentials and your institution will see a lower rate of graduation. But you will also see students completing their undergraduate degrees who would could never have achieved such success elsewhere.

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Black College Presidents February 10, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, African Americans, Blogroll, College Presidents, Current Events, Higher Education, Ruth Simmons, Women.add a comment

Harvard’s decision to appoint it’s first woman president (Drew Gilpin Faust) creates a natural opening for interested observers like me to assess the progress of other marginalized groups in making inroads into academia’s executive offices.

Given that even the most rudimentary level of academic achievement (basic literacy) was illegal for much of our history, African Americans’ success in breaking into the executive ranks of some of the nation’s most presitigious colleges and universities is nothing short of miraculous.

Still, Black campus executives are few and far between. Despite increasing numbers of Black faculty and administrators, obstacles still remain. In “An Overview of African American College Presidents,” Sharon Holmes explains:

Overall, access to educational and employment opportunities for African Americans in general has increased steadily since the turbulent 1960s; however, research indicates that a disparity still exists at various levels of the academic ladder when African Americans are compared to their White counterparts (Corrigan, 2002; Fields, 1991, 1998; Lindsay, 1999; Opp & Gosetti, 2002; Thomas & Hirsch, 1989). Some of the research also provides evidence to suggest that the vestiges of the past linger such that race and gender-related issues make equity, mutual respect, and full participation in all areas of the academy difficult for African American and other administrators of color to achieve (Holmes, 1999, 2003; Turner & Myers, 2000). This is not too surprising considering the long history of “-isms” that have pervaded most social institutions in the United States including institutions of higher education (Esty, Griffin & Hirsch, 1995). For example, Harvey (2001) reports that as late as 1997, African Americans represented only 8.9% of the full-time administrators in higher education, while their White counterparts comprised 85.9%. Similarly, in a study investigating female administrators, Wolfman (1997) found that even though African American women are an integral part of the American society and outnumber African American men as heads of public institutions, they constitute a mere 5% of the overall managerial group in American higher education.

Is academe as receptive to the African American college or university president as it needs to be? Are African American college presidents getting a fair shake in terms of support and compensation? Is African American movement into academia’s highest adminstrative posts happening at an acceptable rate?

Below you will find some of the most current facts and statistics on Black college presidents. Do these numbers paint a picture of progress or stagnation? You decide.

(from the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 12/21/06 )

- In 2001, 7 of the nation’s 2,320 four-year institutions of higher education were led by African American women. (The New Crisis, March/April 2001)

- As of 2002, virtually all HBCUs were headed by people of color. When HBCUs and other minority institutions are excluded, however, the proportion of U.S. colleges and universities headed by people of color drops to less than 10% (American Council on Education, December 9, 2002)

- In 1986, the typical college president was a white male, age 52, married, with a doctorate degree, who had been in office 6.3 years (The American College President: 2002 Edition by Melanie Corrigan)

- The typical college president in 2001 was a white male, age 57, married, with a doctorate degree, who had been in office 6.6 years, and served previously as a senior campus executive. (The American College President: 2002 Edition by Melanie Corrigan)

- In 2002, 6.3 percent of all college presidents were African American, representing more than half of all minority presidents. (The American College President: 2002 Edition by Melanie Corrigan)

- In 2002 Minority presidents were more likely than white presidents to be women. More than one-third of Hispanic presidents (35.2 percent) and one-quarter of African-American presidents (24.2 percent) were women compared with 21 percent of white presidents. (The American College President: 2002 Edition by Melanie Corrigan)

- In 2002 Minority presidents were more likely to lead larger institutions — almost half of African-American presidents and more than half of Hispanic presidents led institutions with headcount enrollments greater than 5,000, compared with less than 30 percent of white presidents. (The American College President: 2002 Edition by Melanie Corrigan)

Posted by Ajuan Mance

Harvard to Name First Woman President February 10, 2007

Posted by twilightandreason in Academia, Blogroll, Current Events, Drew Gilpin Faust, Harvard University, Higher Education, Ivy League, Lawrence Summers, Ruth Simmons, Women.1 comment so far

from Washington Post reporters Valerie Strauss and Susan Kinzie (Saturday, 2/10/07):

Harvard University is about to name its first female president since its founding in 1636, tapping a Civil War historian to succeed Lawrence Summers, whose tenure was marked by controversial remarks about women and clashes with faculty members.

Drew Gilpin Faust, 59, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and a leading historian on the American South, will be formally appointed president as early as this weekend, according to a source with knowledge of the decision.

With Faust’s selection, half of the eight Ivy League schools will be run by women: Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University and Brown University.

Faust, a popular figure on campus known for her collegiality, will succeed the blunt Summers, an economist and former U.S. treasury secretary whose combative five-year tenure as president ended last year. His departure followed a faculty revolt fueled by criticism after he suggested that the shortage of elite female scientists may stem in part from ”innate” differences between men and women.

Many educators said Harvard’s decision would send a message to other major research universities in the country – 14 percent of which are headed by women.

”Harvard is making a statement at a critical time when we are seeing student bodies (at many schools) that are well over 50 percent women,” said Claire van Ummersen, director of the Office of Women in Higher Education at the American Council on Education. ”We see women faculty increasing in number, and the place where we have lagged most is in research institutions having women at the executive level. … Hopefully this will have some influence on boards of trustees or overseers of other institutions.”

At present only one of the eight Ivy League schools has an African American president, Ruth Simmons of Brown University. Still, it is my hope that this move on the part of the United States’ oldest institution of higher learning will inspire other schools to open the ranks of their highest excutive positions, not only to women, but to all groups that have historically been excluded from academia’s most coveted posts.

Posted by Ajuan Mance